Building Drama by Sharing and Withholding

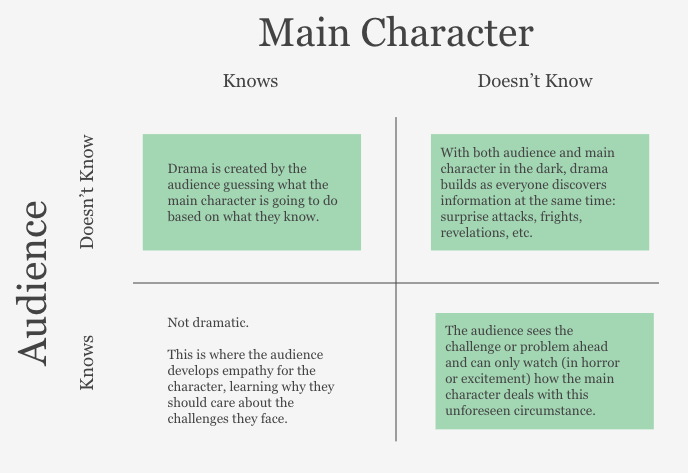

Use the Grid of Drama to build dramatic tension in your stories.

In its most basic form, a story is a flow of information from storyteller to audience. Sometimes, that information is explicit and direct through voice-over narration at the start of the film. Other times, it’s suggested or implied where the audience has to read between the lines.

The main character, or protagonist, of a story is the vehicle in which a storyteller conveys information to the audience. As the character moves through time and space, more information is revealed. But not everything.

A storyteller creates drama by choosing what information to share and what to withhold from the audience - and from the main character.

Drama in storytelling comes from these 3 sharing and withholding dynamics:

-

The main character knows something but the audience doesn’t

-

The audience knows something but the main character doesn’t

-

The main character and the audience don’t know

Behold, the Grid of Drama:

These dynamics can be central to the entire narrative of a story, or they can be just fleeting moments designed to create a comedic surprise, a bone-chilling realization, or a mysterious complication.

Main character knows something but the audience doesn’t.

These are your dramatic moments, usually close to the end of the story where your hero has a plan to stop the evil force. You, however, as the audience aren’t quite sure what they’re going to do yet.

Towards the end of The Truman Show, the main character Truman Burbank disappears from the cameras; he’s nowhere to be seen by the antagonist or by the audience. He has a plan that the audience isn’t in on. After sticking together through the story where the audience and hero share a perspective, this sudden divergence creates unease in the audience; has the hero given up? Their return to the scene and the actions they take to overcome the final challenge often solidify in the audience’s mind why that main character truly is the hero of the story.

Audience knows something but the main character doesn’t.

Depending on the type of movie you’ve either yelled it out loud or whispered it under your breath, “no, don’t go in there.” You know what’s coming but the character you’ve been following doesn’t see it coming. This can be a comedic surprise or a dramatic moment.

Martin Scorcese’s The Departed puts the audience in the unique position of seeing the full picture and letting the worlds of the two main characters collide. There are numerous scenes where the audience is aware of the full dynamic and the drama comes from witnessing how the characters handle the tension in the scene.

Main character and audience don’t know.

This is the go-to in storytelling where the storyteller shares information with the audience at the same time as the main character.

Almost every scene in Saving Private Ryan follows the Tom Hanks character as he traverses war-torn northern France in search of the Matt Damon character. Both the protagonist and audience are in lock-step as they face new challenges together.

Sharing and withholding dynamics start by the storyteller deciding whether a story is told in first person or third person. Are we, as the audience, following along in the shoes of the main character? Or are we witnessing them interact with the world around them?

Both narrative perspectives have benefits and shortcomings. The vast majority of stories you come in contact with are third person because they offer more opportunities to share and withhold information. Storytellers can introduce an antagonist or impending challenge before the main character ever knows. Or they can introduce a factor the main character isn’t considering, like a lack of time, where the audience feels pressure about but the main character doesn’t.

Here’s a bit more on both first and third person perspective.

First Person Narrative

First-person narrative doesn’t have to be told in an “I” voice. In storytelling, first-person narrative has the main character in every scene and the only information the audience receives is the same information the main character receives. What the character sees, the audience sees. What the character experiences, they audience experiences. While few stories are truly first-person narratives, you can look at The Catcher in the Rye, Forrest Gump, 1917, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as examples.

In these stories, there is no secondary plot line that the main character isn’t aware of. Sometimes, the storyteller uses flashbacks to the main character’s past in order to introduce more tension and invite more sharing and withholding dynamics. “What made the character feel that way?” “Why would they think that?”

To pull off a true first-person narrative is a feat of storytelling. When it fails, it can be extremely boring as the audience simply witnesses the main character interact with the world around them. To execute a true first-person narrative, the storyteller needs a captivating and unique story the audience can’t predict; this way, they can rely on two of the three dynamics:

-

The main character knows something but the audience doesn’t

-

The audience knows something but the main character doesn’t

-

The main character and the audience don’t know

In first-person narrative, the audience can’t know something the main character doesn’t know, otherwise, by definition, it would be third-person narrative (which we’ll get to).

Through most of the story, both audience and main character will receive new information at the same time which means the setting, other characters, and plot need to be novel. Think about the single-take war film, 1917 where you follow the main character as he attempts to prevent a surprise attack. The tension of the story: will he make it to the front line in time to prevent the attack? It’s a simple dramatic question that the audience becomes deeply invested in. As they follow over the shoulder of this main character, his mission becomes the audience’s mission.

However, first-person narratives can also slip information by the audience while the main character receives it. These moments remind the audience that the main character is real - that they have their own history, perception, and understanding of their world.

Third Person Narrative

Most stories you interact with are in the third person. You’re witnessing or reading about a character as they interact with the world. While many stories will be based on a character and their experience, they’re not truly first person.

While the vast majority of the Harry Potter series involves Harry in almost every scene, there are numerous moments where the audience is let in on information that Harry is not. We learn about enemies conspiring against him before he’s aware they even exist. The drama builds as we see these enemies present themselves and Harry has to overcome them.

Third person offers flexibility in storytelling.

All three sharing and withholding dynamics are at play in third-person stories. It’s easy for the storyteller to show different storylines coming together or show the protagonist and antagonist’s perspectives of the same event. The main character may learn something that the audience doesn’t realize until later on. In third-person narrative, the audience is truly a fly on the wall.

Both first-person and third-person storytelling have their benefits and shortcomings but both create drama in the same ways:

-

The main character knows something but the audience doesn’t

-

The audience knows something but the main character doesn’t

-

Neither the main character or the audience knows something

When you’re crafting your next story, consider what information you’re sharing with the audience and the main character. What should they know and when should they know it?